2013 and 2014 marked a turning point in the history of globalisation, with several high-profile companies deciding to move their production not to China, but rather back to the USA or Europe. Why?

The answer to this question lies in several factors:

- Shorter delivery time

- Fluctuating demand

- Issues with quality

- The need for specific expertise in some sectors

- The unique nature of some products

- A lack of qualified workforce available locally

- The need for greater coordination between R&D and production

Even though there are still few occurrences of domestic relocation, the paradigm of systematically moving large-scale production operations to China is now being called into question. China’s declining competitiveness as a result of rising direct costs is not being compensated by other low-cost Asian countries. And Eastern Europe remains an alternative few companies choose. But more importantly, increasingly decisive factors like competitiveness, product personalisation, automation and eco-friendly design are weighing toward maintaining or even relocating production domestically.

How do you gauge the potential benefits of domestic relocation? A total cost of ownership approach provides a way to assess hidden benefits. It should be noted that the choice to relocate does not need to apply to the entire production. However, it should be very clear which operations are to be maintained abroad and which to be relocated domestically. The initiative is usually paired with a complete supply chain overhaul. Lastly, a design-to-cost approach applied to both products and production provides an effective way to re-create value when adapting to a domestic industrial context.

China-Based Production, an Increasingly Less Pertinent Choice

Chinese Labour Cost on the Rise

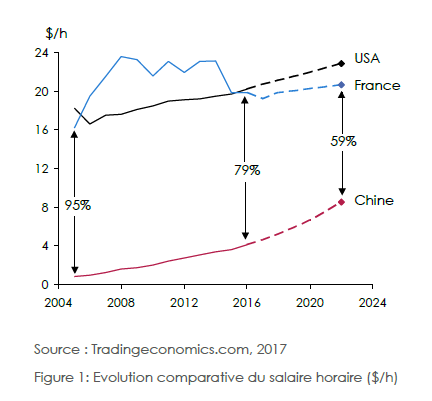

Since 2008, Chinese wages have risen by 13 to 15% annually, as opposed to an annual increase of 1-3% in France and the USA.

The gap is so wide that Chinese workers, who were 20 times cheaper than the French 12 years ago, are only 5 times cheaper in 2017. According to projections, this ratio should drop to 2 or 3 times cheaper by 2022.

In addition, social contributions are also going up, from 23% of an employee’s pay in 2002 to 35% in 2009. The result is a dramatic increase of the total cost of workforce by 15 to 20% over the last ten years.

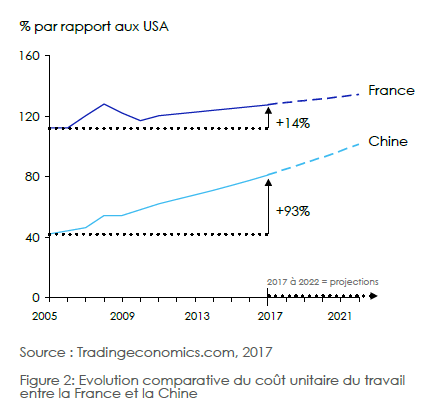

This analysis should also consider labour productivity to establish a comparison based on unit labour cost — i.e. the ratio between hourly labour cost to production output.

The increase of unit labour costs in China has accelerated in the last 10 years, to reach 80% of US unit labour costs in 2017 — a 93% increase since 2005.

For the same output, the cost of labour per unit in both countries is converging. Which means China’s only real value would be its massive production capacity, owed to its large readily available workforce.

Beside labour costs, China is also registering an increase of costs related to transport, real estate, taxes and energy; and the trend is expected to continue over the next five years. This change is a result of the global economic context, Chinese inflation and the Yuan’s appreciation.

A complex supply chain can lead to extended delivery times and higher warehousing costs. Chinese productions are less responsive and less flexible to accommodate requests for rapid design modifications. Because of its geographical distance from Europe and the US, and because of its choice to specialise in high-volume low-diversity products, China is at a disadvantage to respond to fast-changing demand on Western markets. The result is that China’s competitiveness is not clear for time to market goals ranging from 3 to 6 months.

Furthermore, there are still significant risks of intellectual property theft, due to the fact that China has developed its industry on a model based on reproducing products designed abroad.

Even though manufacturing in China can still be the right choice for products intended for high-growth Asian markets, the widely-held opinion that China is the best option for relocating your production is no longer justified.

Delocalize to other countries risky and limited choices

Vietnam, Indonesia: reduced costs but high risks

In some Asian countries, labour costs are still very low, and are increasing at a pace much slowerthan in China. Hourly wages in countries like Vietnam, Bangladesh and Indonesia are still twice to four times lower than in China.

But taking a look beyond financial considerations, the risks we identified in China are even greater in those countries: supply chain complexity and associated costs, longer delays, lower-qualification workforce, lesser quality, low responsiveness and flexibility. These countries’ capacity to absorb China’s current output is also limited by the substantial lack of infrastructures: transport, energy, automation.

Poland, Romania: a limited choice of countries

And what of Eastern Europe, another option closer to domestic markets, where cost and risk factors are less dissuasive? For instance, a growing number of companies are choosing to establish production sites in Poland or Romania. However, there are only a limited number of alternatives to Asian countries and they do not necessarily offer more satisfaction for productions that require high levels of automation, because the labour cost factor becomes insignificant.

Tangible results at each mission

July 17, 2023

The space industry’s path to a sustainable future

July 4, 2023

Measure R&D performance

June 19, 2023

Standardization perspectives of nuclear plants

June 8, 2023